Millions of people worldwide are waiting for a cornea transplant, while their sight worsens. But with funding from Fight for Sight, Dr Hannah Levis and her team are developing an option, which could help people get their eyesight back sooner.

Millions of people worldwide are waiting for a cornea transplant, while their sight worsens. But with funding from Fight for Sight, Dr Hannah Levis and her team are developing an option, which could help people get their eyesight back sooner.

Every year in the UK, 3,000 cornea transplants take place, using corneas donated by people after their death. But for many reasons, there is a shortage of willing donors. Globally, for every one corneal transplant that happens, there are 70 other people in need.

As a result, over 12 million people worldwide are on a transplant waiting list. And while they wait – for months, or even years – their eyesight continues to deteriorate.

According to Dr Hannah Levis from the University of Liverpool, the impact this decline has on everyday tasks and hobbies has a big knock-on effect. “The longer you go on and can’t do those things, it can affect other parts of your life, including your social life and mental health.”

Bio-synthetic grafts

To get around the cornea supply-and-demand problem, Dr Levis has been working with engineers, chemists, and surgeons to develop what they call a ‘bio-synthetic graft’.

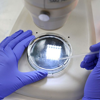

There are two parts to the graft. First, the ‘bio-’ part: Dr Levis’s team extract cells from the inner surface of the cornea and grow them in the lab, multiplying them thousands of times over. Then they attach these cells onto the second part of the graft: a synthetic transparent material, which has the right physical properties for cornea surgery.

Dr Levis’s ambition is, instead of one donated cornea treating one patient’s eye, each cornea could treat 30 or more people. She believes this could cut down waiting times and give people their sight back, sooner.

“Our solution is to create biosynthetic grafts. So instead of one donor cornea you give to one recipient, we can use our biomaterials as a carrier, and create 30 or 40 graphs from that one donor cornea.”

Proving the graft works

Fight for Sight awarded Dr Levis funding in 2017 to prove the biosynthetic graft could be an alternative to donated corneas.

During the project, the team first made sure the graft was suitable for surgery. Working with surgeons, who practiced using the graft with pig eyes, the team optimised the synthetic material to find the right balance between stiffness and flexibility.

Then they tested the graft in animals, and showed it was an effective treatment to correct problems with the cornea.

With the evidence gathered from the Fight for Sight study, in 2022 Dr Levis won a Medical Research Council grant worth £1.4 million. Using this funding, they are updating all their processes so the graft can be manufactured safely and at scale, in preparation for clinical trials in humans.

Cutting waiting times

If all goes smoothly, Dr Levis hopes the first trials could start before 2030. She believes the graft could significantly cut waiting times for a cornea transplant. “You could treat 30 people around the country in one week. So those patients that would have waited months or years for a transplant would be boosted up the list a bit quicker.”

Dr Levis is clear that the Fight for Sight grant was pivotal for their work, helping them translate their idea into something that could potentially benefit millions worldwide.

“Fight for Sight is really one of the only eye charities that gives those sorts of grants out,” she says. “They could see the patient benefit in the long-term.”

“There are so many people in my department that have been supported by Fight for Sight."

Related content